Editorial

Bar raised for economic policy – demographic trend and public debt weigh on national economy

According to the Bank of Finland’s new forecast, the COVID crisis will not cause a substantial long-term drop in the Finland’s GDP. This is clearly good news. Generally, when the economy returns to growth following a deep economic crisis, output does not return to the pre-crisis trend, but to a lower trajectory. This time we expect the outcome will be better. In this respect, the extensive, strong economic policy response to the crisis can be considered a success. The public finances will, however, be left with a long-term scar.

Public debt has grown rapidly during the crisis, and we can expect the debt will continue to grow in the immediate years ahead even after the acute crisis has passed, unless new decisions are taken to strengthen the public finances. With the forecast indicating the cyclical situation next year will be better and the economy growing, fiscal policy should be directed towards improving sustainability. A return to spending limits in practice without unnecessary delay is fundamental to the sustainability of the public finances and the credibility of the spending limits system.

If we look a little further forward, the economic outlook is weaker than in previous decades. We are facing the same opportunities for growth and the same questions around the sustainability of the public finances as before the crisis, but in respect of the latter we could unfortunately be facing more difficult times.

Finland’s problem is visible in the trend of the past 15 years, when we have lagged well behind the pace of the other Nordic countries. And there is no sign that this lost ground will be recovered in the future. The demographic trends make Finland’s position worse.

How have we arrived in this situation? Why has Finland’s economy lagged behind? The international financial crisis of just over a decade ago paralysed international economic developments for several years. But the other Nordic countries faced the same external environment as Finland. So this does not explain Finland’s weaker performance relative to our Nordic neighbours.

In addition to the sluggish international economy, the Finnish economy also experienced several other blows. The electronics and forest industries both experienced a contraction. Other industries did not quickly expand to fill the gap. One reason for the contraction was a more rapid rise in labour costs than elsewhere, which weakened cost-competitiveness and the profitability of export production. The situation was not helped by the decline in the Russian economy. In addition to these setbacks, Finland’s working-age population has been contracting since 2010, which has weakened the economy’s opportunities for growth.

The Finnish economy’s ability to produce new success stories to replace the past glories has also undoubtedly been weakened by factors other than the aforementioned weakening of cost-competitiveness. The causes are likely to lie in the structure of the economy and the economic policies pursued.

Here, we must ask one question. Is it time for us in Finland to stop explaining our problems by reference to the events of 10–15 years ago? Is it time to acknowledge the facts and begin to determinedly address our weaknesses that the Nordic comparison so clearly reveals?

The problems in the economy can be divided into three factors that together determine GDP, and by extension the ability of the public finances to bear debt. These factors are labour productivity, the employment rate and demographic trends.

Average labour productivity was growing relatively rapidly in Finland before the financial crisis, but since the crisis it has been almost stationary.

A contributory factor behind the weak productivity development has been the decline of the electronics industry. Average productivity development in other industries, too, has been weak since the financial crisis when compared with other advanced economies.

Another associated factor has been the weakness of corporate investments in productive capacity. Recent surveys hold out the promise of an improvement, which is positive in itself, but because of the uncertainties surrounding them they do not change the overall picture.

Inputs in research and development, which support innovation and hence productivity growth, have declined in Finland relative to GDP during the past 10 years. The contraction in electronics has had a major impact here, too, but even leaving that to one side, average corporate investment in R&D has been rather weak relative to other advanced economies.

Taking into account how weak Finland’s productivity development has been, there would be good grounds to now increase the incentives to invest in innovation. Extensive and permanent tax incentives for R&D investment would be a good option. This would give general support to the opportunities of different industries and companies to develop their productivity.

Of key significance in regard to innovations and labour productivity is competence and the level of skills. One worrying trend during the past 15 years has been the fact that the average educational attainment of young adults has begun to decline. This is another trend that needs to be reversed.

In contrast to the picture regarding labour productivity, in regard to changes in the employment rate Finland has not lagged behind in Nordic comparisons during the past 15 years. The actual rate has, however, remained well below that of the other Nordic countries. It is questionable whether a Nordic welfare state can be sustainably funded without a higher employment rate, in view of the growth in the population share of elderly people.

Although Finland’s employment rate has indeed risen, particularly among older cohorts, even there it is relatively low. This is one segment of the population for whom it would make sense to seek to encourage a higher rate of employment. Another such group is young adults, for whom the transition from education to working life is not always without its problems. In Finland, the proportion of young adults who are neither in work nor in education has during the past 10 years been the highest amongst the Nordic countries.

In addition to productivity and the employment rate, a third factor that influences GDP is the size of the working-age population. In Finland, this began to decline a good 10 years ago as the post-war baby-boom generation began to reach retirement age.

If we look ahead beyond the next few years, there is no reason in general to expect major differences between the advanced economies in respect of changes in employment rate or labour productivity. In contrast, in regard to demographic developments we can anticipate the future on the basis of the current age structure of the population. The contraction in the working-age population can be expected to continue.

Demographic developments will be influenced by immigration. For decades already more people have been moving to Finland than have been leaving. However, net immigration has been much lower than in the other Nordic countries.

Of course, demographic developments could in the years ahead differ from expectations, in respect of both fertility and net immigration. Immigration in particular can also be influenced by policy decisions, and rapidly.

All in all, Finland’s prolonged lagging behind economic developments in the other Nordic countries is the sum of many factors. In part, it has been the result of bad luck. In addition, the structures of the economy have not always made it easy to adjust to the changed situation. Policy measures have not been effective enough in encouraging change. Fiscal policy has on average been exceptionally expansive, but the problems have been such that the fiscal policy stimulus has been unable on its own to provide a solution.

In order to bring about a sustained improvement in the outlook, structural reforms must continue. There is a particular need for measures that can raise Finland’s employment rate to a good Nordic level. Without new initiatives, the public finances will continue on an unsustainable footing and economic wellbeing threaten to lag permanently behind our Nordic neighbours.

Differences in currency arrangements do not seem to directly explain the differences in economic performance among Nordic countries. The Danish crown has been strictly tied to the euro, while the Swedish crown has floated. In both countries, economic developments have been more positive than in Finland. For a small economy, the euro brings stability to both exchange rates and interest rates. Success requires that the workings of the labour market and the structures of the economy support adjustment when circumstances change.

We cannot decide in Finland on a new rise for the electronics industry or the Russian economy. On the other hand, decisions taken in Finland can influence the incentives for R&D activities, the education system and immigration in pursuit of employment. It is also possible to influence the opportunities for entrepreneurship, new companies’ possibilities to challenge old ones, the possibilities for bargaining at local level, employment incentives, Finnish residents’ opportunities to move in search of work and the arrival of skilled foreign labour in Finland. I raised these issues already in the government discussion on spending limits in April. The lost ground relative to the other Nordic countries can be recovered, and the economy’s ability to adapt to changed circumstances can be improved.

All in all, demographic trends and the inflated public debt now set the bar even higher for economic policy. Recent years have seen several important reforms in the economy in response to the increasingly difficult situation and deteriorating outlook. However, we still need many new decisions. There is a key role for reforms that can boost employment and strengthen the public finances.

Thus, it is largely in our own hands whether we can manage the type of reforms that would bring Finland’s economy and employment back onto a Nordic trajectory that can secure the future of our welfare society.

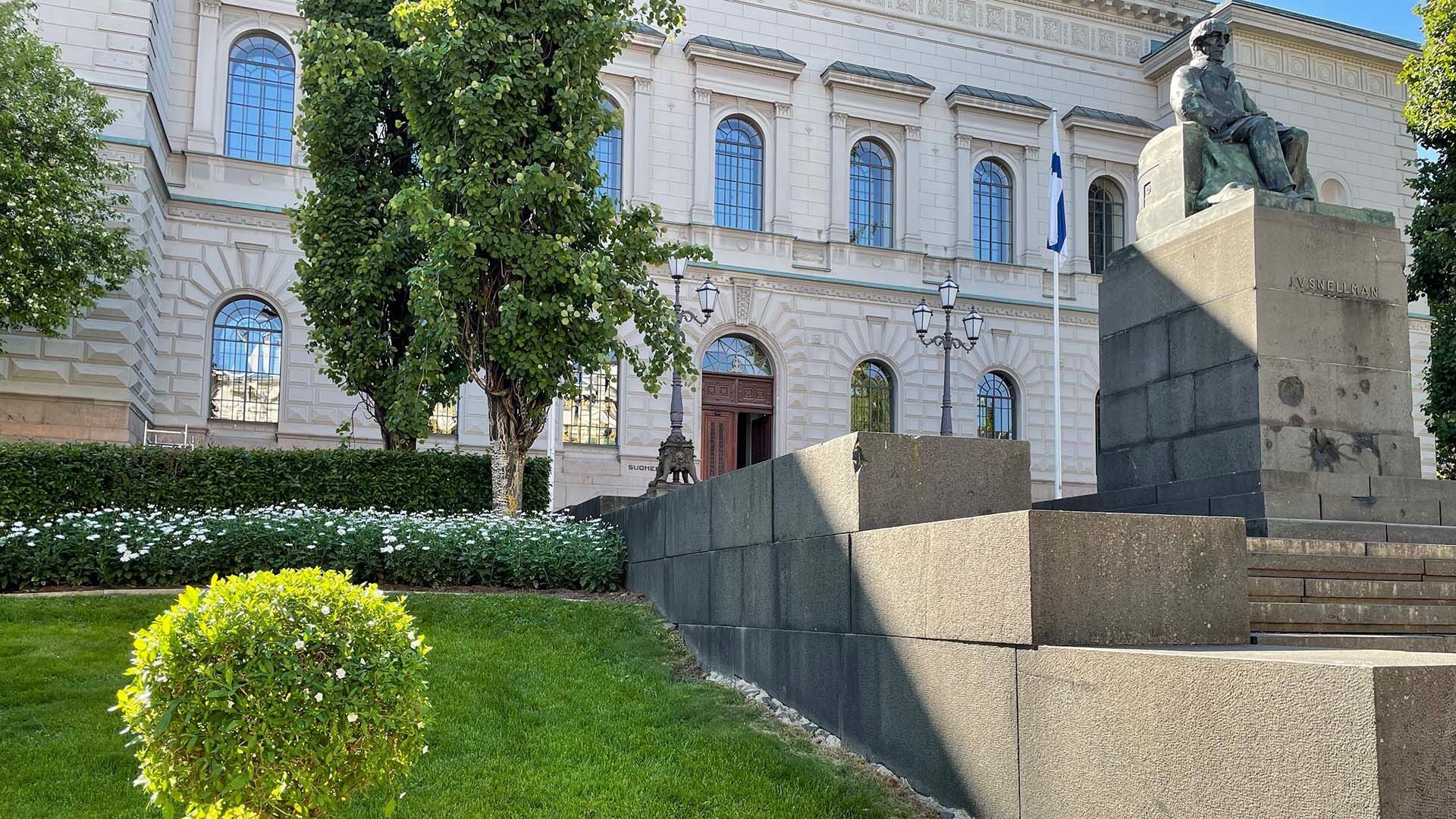

Helsinki, 14 June 2021

Olli Rehn

Governor of the Bank of Finland